Table Of Content

Towards the end of his life his principal journalistic outlet was the Sunday Independent. Professionally he was once again with the loss of his dáil seat on the qui vive. Late in 1977 he embarked on an extended African trip for the Observer, and had a memorable encounter with the Zimbabwean revolutionary Robert Mugabe, who asked him if he supported freedom fighters in his own country. O'Brien replied that if Mugabe meant the Provisional IRA, he had not supported them but favoured their suppression by all lawful means. Mr Mugabe smiled as he spoke.' Mugabe was incensed on the publication of O'Brien's account in January 1978.

Israel, South Africa and international affairs

He condemned killing and maiming conducted by both sides and, while serving in the mid-1970s as minister overseeing Irish broadcasting outlets, he banned Irish Republican Army statements from Irish radio and television. Stocky, urbane and outspoken, “The Cruiser” as he was known to friends, wrote influential books and essays on many subjects; his works include “The Great Melody,” a 1981 biography of British statesman and philosopher Edmund Burke, and “The Siege,” a 1986 history of Israel and Zionism. One of Conor Cruise O'Brien's favourite anecdotes arose from the time some 30 years ago when he was being courted by the Observer to become its editor-in-chief. The message had been passed to him that he should present himself at a distinctly smart block of flats opposite Broadcasting House in Portland Place. There he was to be interviewed by, among others, the former chairman of the paper, the ubiquitous lawyer Arnold Goodman.

Tony Felloni, notorious Dublin heroin dealer, dies suddenly aged 81

Armed with the archive material, one expert concluded Hammarskjöld "knew in advance that the UN was about to take action in Katanga and he authorised that action". A decade before his execution for his part in the Easter Rising, Roger Casement led the campaign exposing the atrocities inflicted by the Belgians, who enslaved millions of natives to cultivate the world's new industrial wonder, rubber. Casement's friend Joseph Conrad captured a taste of this regime of terror in his shocking novel Heart of Darkness which became the movie Apocalypse Now. National Review, April 8, 1996, John Gray, review of On the Eve of the Millennium, p. 53.

Civil Service

Donal Cruise O'Brien obituary - The Guardian

Donal Cruise O'Brien obituary.

Posted: Wed, 31 Oct 2012 07:00:00 GMT [source]

Shortly before Cruise O'Brien arrived, the crisis in the region was made far worse after the murder of the newly independent Congo's first democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. The rulers of one province, Katanga, opted to secede from the newly formed Democratic Republic of the Congo. Although they had officially abandoned their old colony, the Belgians were still anxious to cash in on the great natural resources of the country, and Katanga was a land rich in those resources. It is one of history's great ironies that thousands of Irishmen marched off to the trenches of the Great War on a mission to save "little Catholic Belgium" from German oppression, at a time when Belgium, as colonial master of the Congo basin since the 1880s, was presiding over one of the most brutal and genocidal regimes the world has ever seen. New Republic, September 11, 1965; September 7, 1968; March 3, 1986; September 12, 1988; March 10, 1997, Sean Wilentz, review of The Long Affair, p. 32. Nation, December 20, 1965, p. 502; February 23, 1970; March 27, 1972; March 12, 1973; May 26, 1997, Benjamin Schwartz, review of The Long Affair, p. 29.

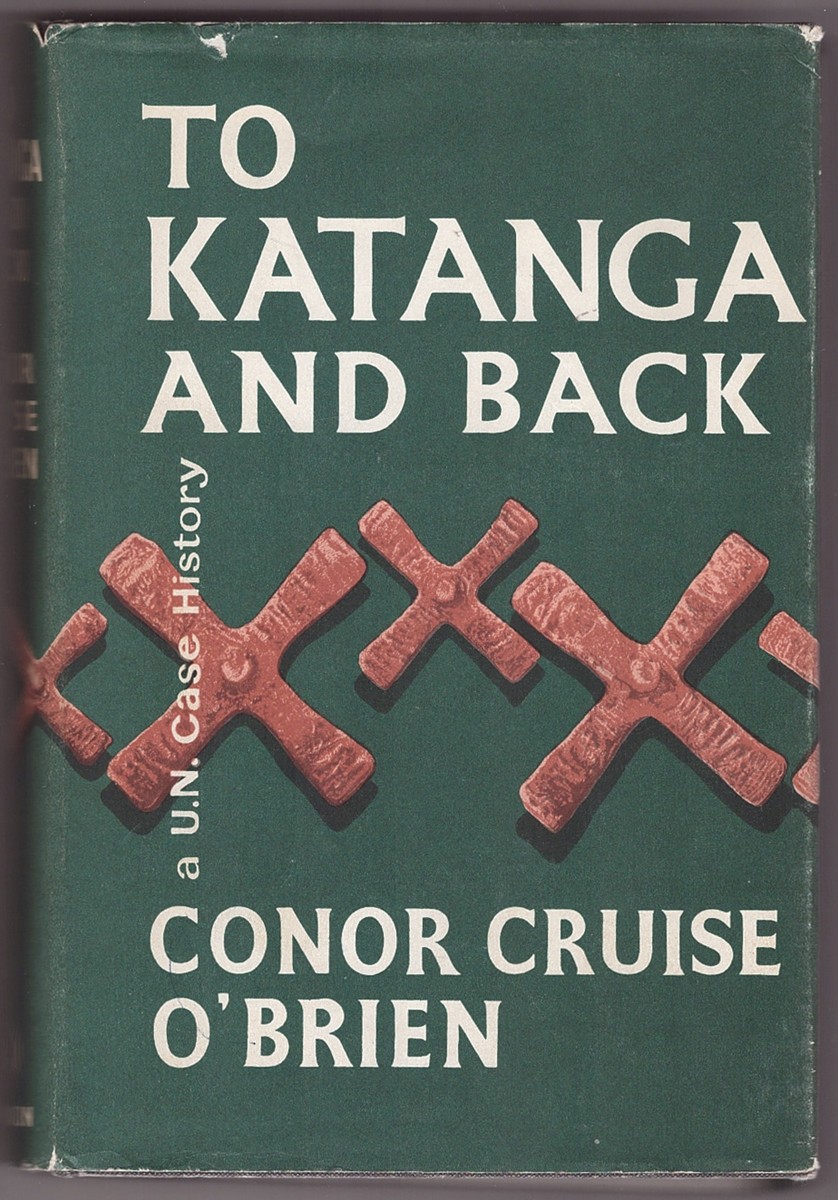

Following his resignation, O'Brien made public his intention to publish a book about the difficulties he had encountered in the service of the U.N. Shortly thereafter, he received a letter from then acting Secretary-General U Thant advising him that unauthorized disclosure of U.N. Thant's letter serves as the preface of To Katanga and Back, an autobiographical narrative of the crisis in the Congo, which O'Brien published in 1963 despite U.N. In 1974–5, further tensions surfaced between O'Brien and his cabinet colleagues, as well as within the Labour Party, as a result of O'Brien's outspoken views on Northern Ireland. A ‘demand for it and insistence that it is on its way’, he protested, ‘actually mitigate against progress towards peace and reconciliation in the here and now’.Footnote 131 By the summer of 1975, O'Brien came into renewed conflict with some of his cabinet colleagues — again FitzGerald was his main antagonist.

The return to Ireland

Eventually he returned to Ireland, where there had been a swing to the left politically, and stood as a Labour candidate in a Dublin constituency. Unexpectedly, he won a big vote and became embroiled with his bete noire, Haughey, for whom he later coined the word Gubu – standing for "grotesque, unusual, bizarre and unprecedented". O'Brien attacked Haughey over his role in the arms crisis, a cause celébre at the time, in which certain Fianna Fail politicians were alleged to have tried to smuggle arms shipments to nationalists in Northern Ireland. In the Department of External Affairs, during the 1948–51 inter-party government, he served under Seán MacBride, son of John MacBride and Maud Gonne, republican and former IRA Chief of Staff, who would become the 1974 Nobel Peace Laureate.

Cruise O'Brien accused a combination of British, French and white Rhodesian elements of attempting to partition off Katanga as a pro-Western client state. He used military force to oppose a combination of western mercenaries and Katangan forces. Days after he green-lighted the aggression, as the Siege of Jadotville raged, Hammarskjöld was killed in a plane crash, leaving Cruise O'Brien to carry the can. He was swiftly let go by the UN, at the request of the Irish government, and he resigned from the diplomatic corps. Cruise O'Brien's version of events, set out in his 1962 book To Katanga and Back, has been dismissed as highly selective and self-serving, and while it deliberately excluded crucial items, recent evidence from the UN archives suggests Cruise O'Brien was acting with the express approval of Hammarskjöld.

Like Charles Haughey, who would become his bête noire in later life, Cruise O'Brien was a star scholar who breezed through academic life nearly always at the top of the class. The Belgians turned the Congo into a real-life hell on Earth, and when they pulled out in 1960, they left behind an unholy mess which the Irish, wearing their UN berets alongside a force of Swedes, were supposed to somehow sort out. Over a five-year period some 6,000 Irish soldiers served in the Congo, with 26 of them killed in action. Conor Cruise was posted to the Congo in 1961 as the special representative of the United Nations' charismatic Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld. He was still in his early forties and he already had a glittering career behind him. Contributor of articles to periodicals, including Atlantic, Nation, New Statesman, and Saturday Review.

With Máire he campaigned against the Vietnam war, and sustained in December 1966 a severe kick in the hip from a New York policeman ('no prizes for guessing his ethnicity') at an anti-war demonstration in Manhattan at which they were both arrested. He was consistently critical of the passivity of American policy towards South Africa and Rhodesia. He visited Biafra in mid-September 1967, and asserted the rights of the Ibo in an extended piece for the New York Review of Books, and in the Observer, rejecting any equation of Biafra with Katanga. He supported Senator Eugene McCarthy's anti-Vietnam war campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968. His concise and brilliant, if coldly unsparing, Camus (1970) belongs to his New York period.

The issue on this occasion was O'Brien's attitude to possible British withdrawal from Northern Ireland. Following the burning of the British embassy in Dublin, on 2 February 1972, he claimed that ‘I reverted to my former view, which has been my view ever since’. British withdrawal, he maintained, would lead to ‘full scale civil war’.Footnote 134 O'Brien held firm to this position for the remainder of his life. Politically his stance to the left of mainstream liberal intellectuals reflected the complex interrelationship of the unfolding of his own thinking to the international politics of the 1960s. In his essay 'Contemporary forms of imperialism', published in autumn 1965 in the review Studies on the Left, he attacked neo-colonialism not as driven by economic interests, but as a modern form of racially premised domination, promoted through ideas of the containment of communism. In the spring of 1966 he condemned indiscriminate anti-communism in an essay entitled 'The counterrevolutionary reflex'.

Two additional notable incidents affected Cruise O'Brien's career as minister, besides his support for broadcasting censorship. In 1962, Cruise O'Brien married the Irish-language writer and poet Máire Mhac an tSaoi in a Roman Catholic church. Cruise O'Brien's divorce, though contrary to Roman Catholic teaching, was not an issue because that church did not recognise the validity of his 1939 civil wedding.

His involvement on the anti-partition side ceased with his appointment to the Irish embassy in Paris, where he was counsellor (1955–6). In 1969, as a Labor candidate, he won a seat in Ireland’s Parliament representing Dublin Northeast. Regarded as left-wing by Irish voters, he soon surprised many of his supporters with the provocative and highly influential book “States of Ireland” (1972), in which he attacked what he saw as the myths of the Republican movement and excoriated the nationalist dream as sectarian and colonialist. As minister of posts and telegraphs in the coalition government that formed in 1973, he banned Sinn Fein from the airwaves.

Like his friend Michael O'Leary he never truly ceased to be of the Labour party ('Saints, sinners and sincerity', Magill (July 1981)), though his attacks on Dick Spring's driving forward of the peace process were unsparing. O'Brien was the Labour party spokesman on foreign affairs and Northern Ireland, and part of a Labour delegation that went to the North in August, meeting as he later noted only nationalist representatives. He rapidly fell out with Noel Browne and David Thornley (qv); his relations with his third roommate in Leinster House, Justin Keating (qv), took longer to sour. Sustained loyally by Corish, Frank Cluskey (qv) and Michael O'Leary (qv), he continued to visit Northern Ireland, and on 12 August 1970 was beaten up at an Apprentice Boys' rally at St Columb's Park in Derry. Born in Dublin on 3 November 1917, O'Brien's career encompassed roles in the Irish civil service and then the UN, where he came to the attention of the secretary general, Dag Hammarskjold, who tasked him with leading the peace keeping operation in the Congo in 1960. O'Brien, who led the United Nations operations in the Congo in 1960, was Ireland's minister for posts and telegraphs in the mid-1970s and who became editor-in-chief of the Observer newspaper in 1979 for three years, died last night.

He was active in the college debating society, edited the college magazine, and joined the Fabian society and the Labour party. The UN was supposed to provide a neutral buffer, but archive records released many years later show that the head of the UN, Dag Hammarskjöld, was fiercely pro-Western/anti-Communist and covertly gave his full backing to UN aggression towards the breakaway Katangans. Swede Hammarskjöld's top man on the ground was Ireland's rising star of the diplomatic corps, Conor Cruise O'Brien, who was left, after his boss was killed during the crisis, to carry the can for a blot on the copybooks of both Ireland and the UN. When Belgium officially relinquished its colony in 1960, it left behind a legacy of slavery and plunder.

O'Brien was a maverick, both as a writer and politician, and to accuse him of inconsistency is beside the point. Some shrewd analysts viewed him as a fine intellectual led astray into public life by ambition and the desire to prove himself a man of action. Others saw him as a courageous radical nonconformist who challenged the forces of obscurantism. It is certainly arguable that, like Burke, he began as a Whig radical and ended up as almost a reactionary. The warring aspects of his personality partly had their roots in old Parnellite and home rule politics, which personalised and sometimes embittered public debate, partly in the example of the generation of French intellectuals that emerged after the second world war, partly in the liberal leftism of the 1950s, and partly in 1960s protest politics. But the crucible of all these was his own mercurial, restless personality and intellectual brilliance, backed by a historian's sense of history and the born journalist's flair for being in the wrong place at the right time.

In the aftermath, as the United Nations hastily repudiated the mission, Mr. O’Brien took the fall and left the world body. He recounted his version of events in “To Katanga and Back” (1962) and later wrote “Murderous Angels,” a play about Hammarskjold and Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s murdered premier, which was produced in Los Angeles and New York in 1970. With the Troubles raging in the North, his position made him a hate figure for many Irish, as did his later opposition to the peace effort aimed at bringing Sinn Fein into the government of Northern Ireland. In one, he was kicked by a policeman, and was in considerable pain for days afterwards. During this period, his play Murderous Angels was staged in Los Angeles and later had a brief run in New York – allegedly after black militants had brought pressure on some of the actors to pull out. He had become a hot potato, and the controversy continued when he later published his version of events in the book To Katanga and Back.